NoLand RS11, analog to NMEA 2000 engine monitoring

What follows is a first time guest entry by regular Panbo commenter Adam Block, who is planning a 2011 Pacific crossing aboard his Nordhavn 47 Convexity. Adam says "he had no idea what he was getting into when he started a recent electronics up...

What follows is a first time guest entry by regular Panbo commenter Adam Block, who is planning a 2011 Pacific

crossing aboard his Nordhavn 47 Convexity. Adam says "he had no idea what he was getting into when he started a recent electronics upgrade," but he did manage to convert analog (generator) engine data into NMEA 2000 for display in the N2KView software above and elsewhere. He's also written a clear explanation of the options available for this tricky task, and the specifics of the NoLand RS11 he used...

I'm deep into the secondary projects - nice-to-haves

like external IP

cameras and

centralized systems monitoring. I'm using Maretron N2KView

software for monitoring, but any modern NMEA 2000 digital gauge --

Maretron's own

DSM250 or the Garmin GMI 10, Raymarine ST70, or the "coming

soon" Furuno RD33 -- can display a wide range of data about onboard

systems

ranging from engines to battery banks.

Today

I'm thinking about engine data. Though Convexity

has a single primary engine, we actually have three diesel motors on

board. The

other two are a wing (get-home) engine and a 12 kW generator. Getting

engine

data onto the NMEA 2000 bus (and from there onto one of those displays)

can be easy

or hard, depending on the kind of motor you have. Owners of larger

outboards

have it easy: Mercury, Suzuki, Yamaha, Evinrude, and Honda all output

lots of

engine parameters in NMEA 2000 format, though you may need a funky

wiring

harness or digital gauge to make the backbone connection.

In general the same can be said for modern

electronically-controlled diesel prime movers; most support an engine

data

protocol called J1939 that runs over the familiar industrial CanBUS

(which

happens to be the same wiring and communications standard on which NMEA

2000 is

based). J1939 can be used to exchange data between two engines (to

synchronize

RPMs on a twin-engine vessel, for example) or to drive physical gauges --

Convexity's

analog-looking engine gauges actually receive digital signals via

CanBUS. J1939

engine messages aren't the same as NMEA 2000 engine messages, but

Maretron

offers the J2K100

converter box to bridge the two networks together. (It's a one-way

bridge: the

J2K100 passes J1939 data from the engine network to the NMEA 2000 bus,

but no

information flows the other way).

That's all fine for folks with brand new boats, you

say, but

what about the thousands of sail- and powerboat owners with older

engines that

lack electronic fuel injection and the engine computer needed to output

digital

performance data? Or in my case, what about my Lugger wing engine and

Northern

Lights generator, neither of which supports digital gauges? If I'm

adding a

complete monitoring system to the boat, it seems wrong to exclude them.

(This

is especially true of the generator, as its gauge package is in a

hard-to-see

location near the top of the stairs to the staterooms.)

It took some research, but I came up with three

possible

solutions for getting NMEA 2000 data out of my analog engines:

- Maretron

EMS100:

This analog adapter is designed for Yanmar engines, and Maretron doesn't

currently certify its use with motors from any other manufacturer. They

did helpfully send me a Yanmar engine wiring diagram in case I wanted to try

and make up the required harness on my own, but one look at the diagram's

maze of lines quickly put me off that idea. - NoLand Engineering

RS11:

Browsing through the 2010 Gemeco catalog, I stumbled on a product (and

manufacturer) I'd never heard of. NoLand is a small Florida outfit that

makes a

variety of mostly NMEA 0183 splitters and multiplexers. Their new RS11

converts

the voltage signals many analog engines use to drive gauges into NMEA

2000

PGNs. The RS11 can be configured for a range of different input types

and at

$230 is a relative bargain. - Albatross

ALBA-Engine:

Albatross is a Spanish company that makes some interesting NMEA 2000

sensors

and interfaces (they also appear to distribute NMEA 2000 devices from

nearly

all the other big names in this category, including Actisense, Maretron,

and

Airmar). Unlike the RS11, the ALBA-Engine works with either resistive or

voltage senders. But Albatross is hard to find in the U.S., and their

stuff is

correspondingly expensive - the ALBA-Engine costs nearly $500. {Panbo discussion and slide show here.}

Based on price and capabilities -- my gauges are

voltage-based

-- the RS11 seemed a good fit. I ordered direct from the NoLand web site,

and

the unit arrived about a week later. In the box was a small circuit

board with

a terminal strip on one side and an attached NMEA 2000 drop cable, a

serial

cable (the RS11 needs to be programmed before use via Windows PC), a

somewhat

flimsy-feeling plastic circuit board cover, and one of those business

card-sized CD-ROMs that only work in slot-loading drives.

You can wire the RS11 directly to your engine, but I

found

it much simpler to connect to the back of the engine gauges themselves;

all of

the pickups are in one place, and I prefer to work in the comfort of the

pilothouse than the confines of the engine room. I started on the

generator

first. All of the gauges have standard male disconnects on the back. The

quick

and dirty approach for small gauge sense wires -- I used a short length

of

8-conductor 18-gauge Ancor data cable -- is to just bend the conductor

over the

disconnect tab and then press the female connector on the engine wire

down over

the tab. This approach won't pass any good electronics installer's

muster,

though, and probably violates half a dozen ABYC regulations; the right

way is

to use a standalone

piggyback

adapter, or a female

disconnect

with a piggyback connector as shown in the photo below. The RS11

needs only a single sense wire per gauge, which normally connects to the

'S'

pin on the gauge body; as a ground reference it uses the ground pin of

the

attached NMEA 2000 cable. The NMEA 2000 bus supplies power to the unit.

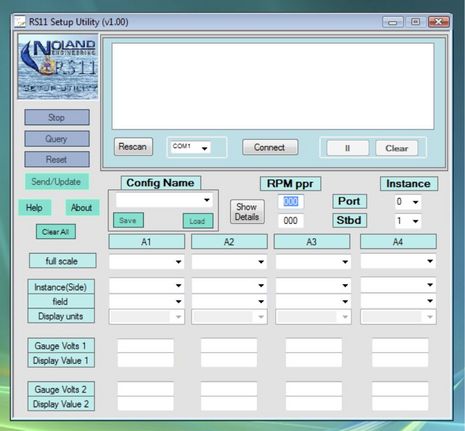

Engines and their gauges vary widely, so before it

will

output accurate data you have to calibrate the RS11 using the somewhat

rudimentary Windows application shown below. The terminal strip has two

tachometer inputs and four analog inputs. With some limitations, the

analog

inputs can be used to monitor any of the following: oil pressure; oil

temperature; engine (coolant) temperature; coolant pressure; fuel

pressure;

alternator voltage; turbo boost; and tilt/trim. Not all engines will

output all

of this data, and with only four inputs you'll have to choose which of

these

are most important. (The RS11 can also be connected to two separate

engines, in

which case you divide the four inputs between the two engines.)

Monitoring RPM requires knowing the number of

"pulses per

revolution" output by the engine. This varies depending on the engine

type, and

the RS11's manual does a pretty good job explaining what information you

need

to properly calibrate the unit. In my case I needed to know the number

of teeth

on the flywheel; a quick inquiry to Lugger provided the answer (126),

which I

entered into the configuration utility.

Analog calibration is a bit more complex. The RS11

operates

on the principle that there is a direct straight-line relationship

between

voltage at the back of the gauge and the actual value being monitored.

In order

to determine this relationship, you enter two voltages and actual values

into

the calibration software, which then derives the proper formula (in the

form value

= m ´ voltage + b,

where m

and b are constants) from the supplied data. For example, in the

case of

engine coolant temperature my measurements were as follows:

Actual temperature #1: 58° F

Measured voltage #1: 6.20V

Actual temperature #2: 110° F

Measured voltage #2: 2.33V

Collecting these numbers can be a bit of a chore,

especially

if they are changing as you measure them. In the case of the engine

temperature, I assumed that "actual temperature #1" was simply the

ambient

temperature of the engine room before I started the engine (it had been

shut

down for a few days). I turned on power to the engine and probed the

back of

the gauge with my multimeter to determine "measured voltage #1". For

"actual

temperature #2" I started the engine and waited for it to warm up enough

to

show a reading on the analog gauge. I probed the voltage at the same

time as I

read the temperature off the gauge, and entered the second set of

numbers into

the configuration utility. Needless to say, analog gauge accuracy,

parallax, and

timing all contribute to the quality of the calibration. Values that

don't

change much over time, such as oil pressure, are easier to calibrate.

With the calibration data entered into the

configuration

utility, it was time to download it to the RS11. I had some trouble

here: the

RS11 refused to accept the new settings. NoLand's head engineer

suggested that

a reboot or two (disconnect the NMEA 2000 cable to cut the power, then

reconnect) should fix the problem, and it did. Seconds later my

generator's temperature,

oil pressure, and output voltage popped up on the Maretron N2KView

screen (seen at the top of the entry).

As you can see, my calibration was pretty good, as

the

displayed values closely track the analog gauges:

Final mounting of the RS11

interface was easy due to its small size (3" x 3.75")

and light weight; I simply mounted it to the back of the breaker cabinet

and

cinched down the cables:

With

a little patient calibration, the RS11 is easy to install and works as

promised, though I did have a couple of issues. First, on at least one

occasion

the RS11 seemed to lose its sensing capabilities. After I left the

engine shut

off for a few days (but the NMEA 2000 network, and thus the RS11, still

powered

up), when I restarted the engine the unit sent no engine data. Rebooting

the

RS11 cleared up the problem but it's something I'll be keeping an eye

on.

My

other issue arose from the nature of the algorithm the RS11 uses to

calibrate

analog voltages. Some analog gauges use inverse voltage; that is, when

the

voltage from the engine's sender drops, the value displayed on the gauge

increases. This is the case for our generator's coolant water

temperature. When

the RS11 is calibrated, the formula it derives for this kind of gauges

has a

negative slope (that is, in that equation above, y is negative).

The

problem arises when the engine is turned off, and the voltage measured

by the

RS11 is zero. This zero voltage is spurious - it's not a true output

from the

engine, but an artifact of the engine being off - but based on the

formula in

the RS11 it appears that the temperature is very high. In our case the

N2KView

gauge reads 254° when the engine is shut down. I spoke to NoLand about

this

issue, and suggested that the unit sense when it the attached engine is

off.

Their chief engineer confirmed they would like to add that feature - one

I

believe the ALBA-Engine does have - but that working within the

limitation of

the small amount of memory on the RS11's circuit board was a challenge.

How about a Panbo round of applause for Adam Block {ed}